Despite decades of advancement in treatment, cancer spreading to multiple parts of the body remains one of the biggest challenges facing patients and their health care teams.

This is particularly true for osteosarcoma, the most common bone cancer in children and teenagers. While survival rates are approximately 70 per cent for people with localized disease, there is a high risk of metastatic spread to the lungs, after which the odds of survival fall dramatically to 20 per cent or less.

Now, scientists at BC Cancer have identified a potential drug that could halt osteosarcoma’s spread. In a study published in Clinical Cancer Research, the researchers demonstrate that the compound can reduce lung metastasis in mice by over 90 per cent, while also shrinking the primary tumour site.

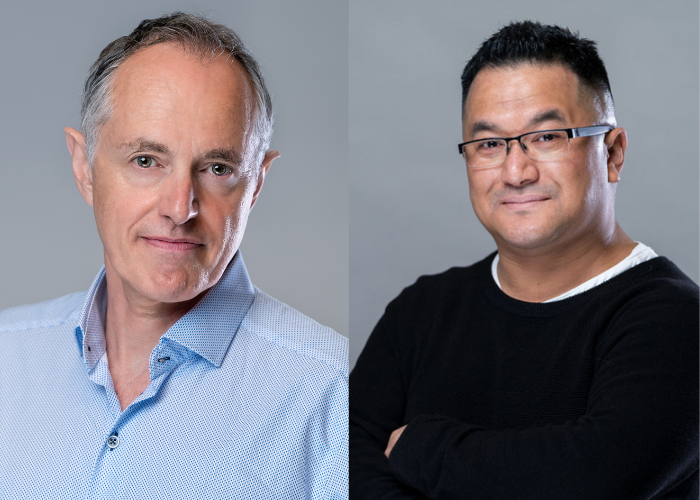

“This discovery brings much needed new hope to children and youth battling osteosarcoma,” said Dr. Poul Sorensen, distinguished scientist at BC Cancer, investigator with the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute, professor at UBC’s faculty of medicine, and the study’s senior author. “We know how devastating this disease can be if it spreads to the lung, and have long needed effective tools to prevent and treat that. With this drug we might be able to stop lung metastasis and give young people a much better chance at beating this disease.”

The drug, known as an eIF4A1 inhibitor, blocks the ability of osteosarcoma cells to protect themselves and survive in the lung’s harsh microenvironment.

The lungs are known to be an inhospitable environment for foreign cancer cells, with the majority being killed by nutrient deprivation and exposure to high levels of oxidative stress. However, in some cases, a small number of cells are able to adapt to such conditions and seed the growth of a metastatic tumour.

“It really only takes a small population of osteosarcoma cells to adapt, survive and proliferate in the lung,” said first author Dr. Michael Lizardo, a scientist in the Sorensen Lab at BC Cancer. “This drug essentially strips those cells of their protective armour so that they’re more susceptible to oxidative stress and unable to take root in the lung.”

As part of the study, the researchers showed that some osteosarcoma cells are able to survive within the lung by producing a protein, NRF2, that acts as a protective antioxidant. They identified the pathway by which the protein is produced and collaborated with the late Dr. Jerry Pelletier of McGill University, who pioneered the development of an eIF4A1 inhibitor compound (CR-1-31B) that disrupts that process.

Dr. Sorensen and his team tested the CR-1-31B compound in mice in collaboration with Dr. Alejandro Sweet-Cordero from the University of California San Francisco, who provided cell lines of metastatic osteosarcoma from his lab.

Notably, a second eIF4A1 inhibitor drug, called Zotatifin, also proved successful in halting lung metastasis and has already shown promise in early clinical trials for other conditions. Dr. Sorensen says this could accelerate its potential for human trials in osteosarcoma patients.

“It’s particularly exciting that there is an existing clinical-grade compound. That opens up opportunities to rapidly begin testing this in human trials and could accelerate timelines for a new treatment to reach patients,” he said.

Dr. Sorensen and his team are now in conversations with clinical researchers to bring the promising discovery into human trials. If successful, it could represent a major breakthrough for children and families affected by osteosarcoma, while Dr. Sorensen also notes that there could be implications for treating a range of other cancers that exhibit similar characteristics, such as some forms of lung, breast and pancreatic cancer.

The study was supported by the BC Cancer Foundation, Alex’s Lemonade Stand Foundation, and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

This article has been adapted from its original version. Read the UBC Faculty of Medicine article here.