Scientific Highlights

1. Developed B9, an IL-6-dependent cell line that is and has been instrumental in the IL-6 field.

Following my training as MD, I worked for 2 years as a research fellow in the laboratory of experimental surgery at the Erasmus University in Rotterdam on a tumor immunology project (19,20). During this time I reproduced the hybridoma work described by Kohler and Milstein (21) for which these investigators got the Nobel prize in 1984. Based on my self-taught hybridoma expertise, I was hired as a research fellow in 1979 to set up monoclonal antibody technology in the Central Laboratory of the Blood Transfusion Service in Amsterdam, the premier immunology laboratory in the Netherlands. There I developed novel immunoperoxidase assays to detect cell surface antigens (22,23) and made several monoclonal antibodies which were used in the International Workshops to define common Clusters of Differentiation (CD) antigens. For this workshop we had to submit large amounts of antibodies, which was not a problem except for one hybridoma that could only be expanded in the presence of tissue culture medium conditioned by endothelial cells (24). We later found that this hybridoma (B9) maintained a strict requirement for IL-6 for growth (25, 26, 27). This line has been instrumental in the IL-6 field ( >1200 citations). A Canadian twist to this story is that I could convince Jack Gauldie from McMaster University that the hepatocyte stimulating factor he was working on most likely was IL-6, a prediction which turned out to be correct resulting in a nice paper (28) and US patent No. 4,973,478.

2. Discovered tetrameric antibody complexes, reagents that are key to the success of the Canadian biotech firm StemCell Technologies in Vancouver

In Amsterdam I made monoclonal antibodies to peroxidise to link peroxidase to cell surface antigens via monoclonal mouse antibodies and polyclonal antibodies specific for mouse IgG1 (22,23). Based on the bivalency of IgG antibodies and the presence of two identical heavy chains in antibody molecules, I speculated that selected monoclonal antibodies specific for epitopes present on the heavy chain of immunoglobulin molecules might be able to cross-link two monoclonal antibodies into a stable tetrameric antibody complex. To test this hypothesis, which turned out to be correct, I made (rat) monoclonal antibodies specific for mouse IgG1 (29). See Figure 1.

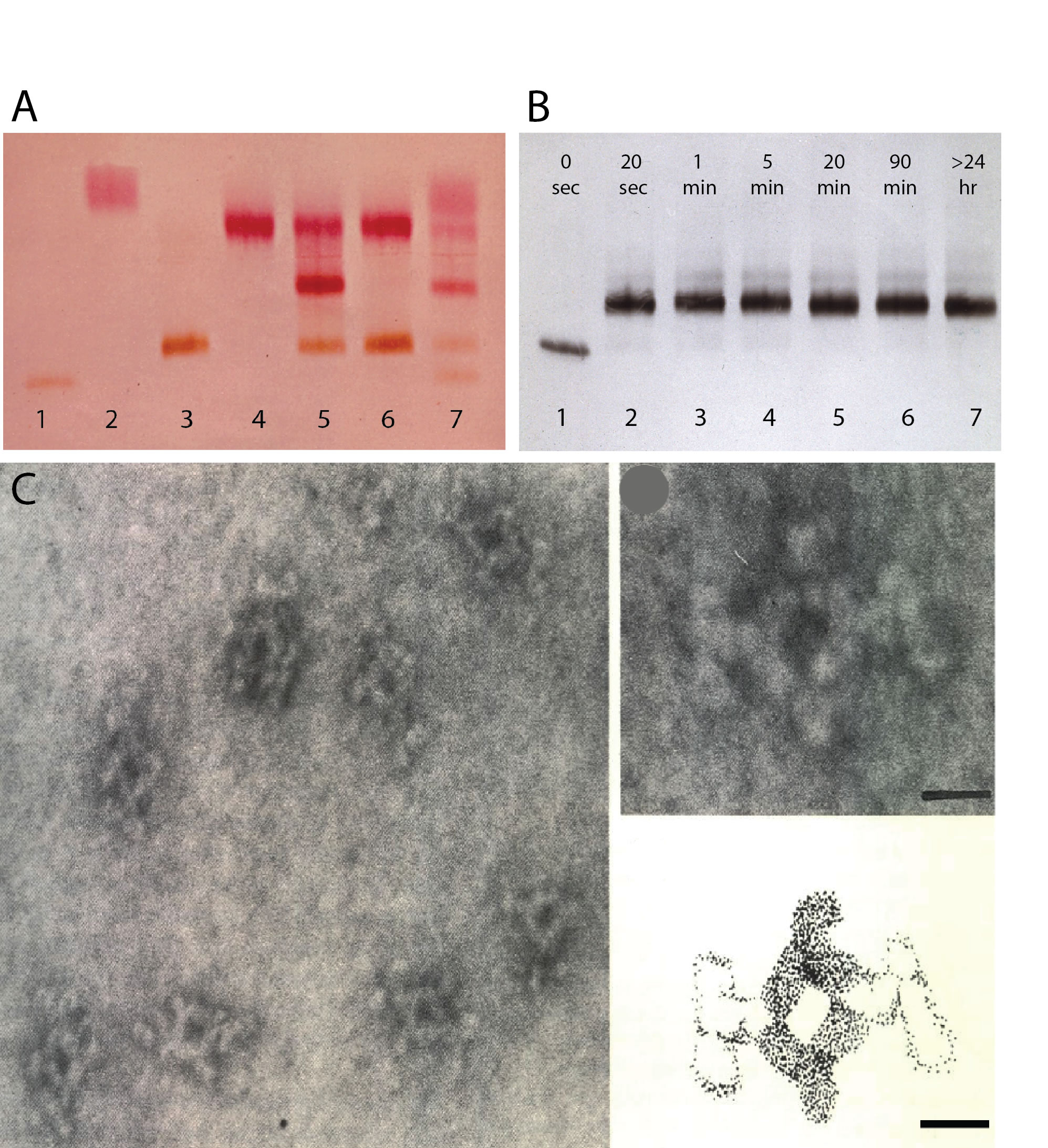

Figure 1. Tetrameric complexes of monoclonal rat and mouse antibodies (from (29). A. Enzyme blot using enzymes and their substrates following agar electrophoresis of mouse IgG1 anti-enzyme antibodies before and after addition of monoclonal rat anti-mouse IgG1. Lane 1: mouse IgG1 anti-peroxidase (a). Lane 2: mouse IgG1 anti- alkaline phosphatase (b). Lane 3: (a) plus an equimolar amount of rat anti-mouse IgG1 . Note: no free mouse antibody. Lane 4: (b) plus rat anti-mouse IgG1. Lane 5: equimolar amounts of (a) and (b) mixed before addition of an equimolar amount of rat anti-mouse IgG1. Note middle band with bispecific monoclonal tetrameric antibody complexes. Lane 6: A mixture of the complexes shown in lane 3 and 4. Note the absence of bispecific complexes. Lane 7. As lane 5 with a limiting amount of rat anti-mouse IgG1. From top to bottom: free (b), (bxb), (axb), (axa), free (a). B. Time course of tetrameric antibody complex formation. Mouse IgG1 anti-peroxidase (lane 1) was mixed with an equimolar amount of monoclonal rat anti-mouse IgG1. At the indicated time points the mixture was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis and anti-peroxidase was vidualized after blotting as in A. Note that antibody complexes are formed within seconds and not affected by electrophoresis. C. Scanning electron microscopy of purified tetramolecular antibody complexes. Scale bar 10 nm.

The ability to easily crosslink two different monoclonal antibodies into very stable tetrameric antibody complexes (US patent No. 4,868,109) has found numerous applications in biotechnology. For example, we described applications in cell separation (30,31) and fluorescent labeling of cell surface antigens (32). Importantly, tetrameric antibody complexes are key to the cell separation technology commercialized by StemCell Technologies in Vancouver and currently employ hundreds of Canadians.

3. Produced several widely used monoclonal antibodies for stem cell research (e.g. CD34, CD90).

In Amsterdam my research interest shifted from immunology to stem cell biology and purification of blood-forming stem cells using monoclonal antibodies became a key research objective. At the time, it was believed that purified stem cells, together with defined culture conditions, would allow unlimited expansion (self-renewal) of stem cells for clinical purposes such as gene therapy and transplantation. During a meeting in London I met with Allen Eaves, who was the director of the Terry Fox Laboratory at the time. Allen convinced me to visit Vancouver and, eventually, to do postdoctoral work which was enabled by a Terry Fox fellowship. In Vancouver we made several monoclonal antibodies relevant for stem cell research including antibodies to CD34 and CD90. Our antibodies proved to be superior reagents to detect e.g. CD34 cells in peripheral blood (33) and identify and isolate stem cells in combination with antibodies to CD38 (34). Our CD34 hybridomas were licensed to Becton Dickenson.

4. Developed serum-free culture medium and novel assays for hematopoietic stem cells

Before the use of xeno-transplants, hematopoietic stem cell activity was primarily measured by the ability of cells to produce colony forming cells in long-term “Dexter” cultures (35). Together with Connie Eaves and Heather Sutherland we established an assay for human cells capable of initiating long-term cultures (36) using the limiting dilution principles routinely used for production of monoclonal antibodies. This assay was used to purify “candidate” stem cells and to develop a serum-free culture medium for stem cells (37). Our medium is commercialized, essentially unchanged, as “StemSpan” by StemCell, another example of a useful product coming from my laboratory.

5. Discovered that self-renewal properties of stem cells are developmentally controlled

Despite our novel antibodies, innovative cell purification techniques, improved culture media and assays for stem cells, our attempts to expand adult blood-forming stem cells in culture were a dismal failure. While it was possible to keep CD34+ cells alive for long periods in cultures supplemented with various cytokines, we could not markedly increase the number of CD34+ cells when cultures were initiated with purified “candidate” stem cells from adult bone marrow (38). A breakthrough came when we finally tested “candidate” stem cells from fetal liver and umbilical cord blood in our cultures. CD34 cell numbers increased several thousand-fold in fetal liver cell cultures and several hundred-fold in cord blood cultures. We concluded that the self-renewal properties of stem cells are developmentally controlled (1). Despite our report of similar findings with purified murine stem cell candidates (39), our findings were essentially ignored only to be “rediscovered” about a decade later (40,41).

6. Discovered that blood-forming stem cells lose telomeric DNA with each division

The failure to significantly expand adult bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells in tissue culture was a set-back for therapeutic strategies that would require significant production of stem cells. The situation did not improve when we found that hematopoietic stem cells also lost telomeric DNA with each cell divisions (2), similar to observations with cultured human fibroblasts (42).

7. Developed quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (Q-FISH) techniques

My questions about the role of telomeres in biology were frustrated by the Southern analysis technique used to measure of telomere length which was laborious and required millions of cells. During a sabbatical in the laboratory of Hans Tanke in Leiden, I started to explore fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) techniques to measure telomere length. The breakthrough came when I could get my hands on novel, synthetic “peptide nucleic acid” probes (43,44). Briefly, I found that FISH could be made quantitative (Q-FISH) using PNA probes under stringent, low ionic strength conditions, that allow PNA, but not competing single stranded DNA, to anneal to the selected target sequences (45) and US Patent No 6,514,693.

8. Reported that telomerase KO mice lose around 5kb of telomeric DNA per generation

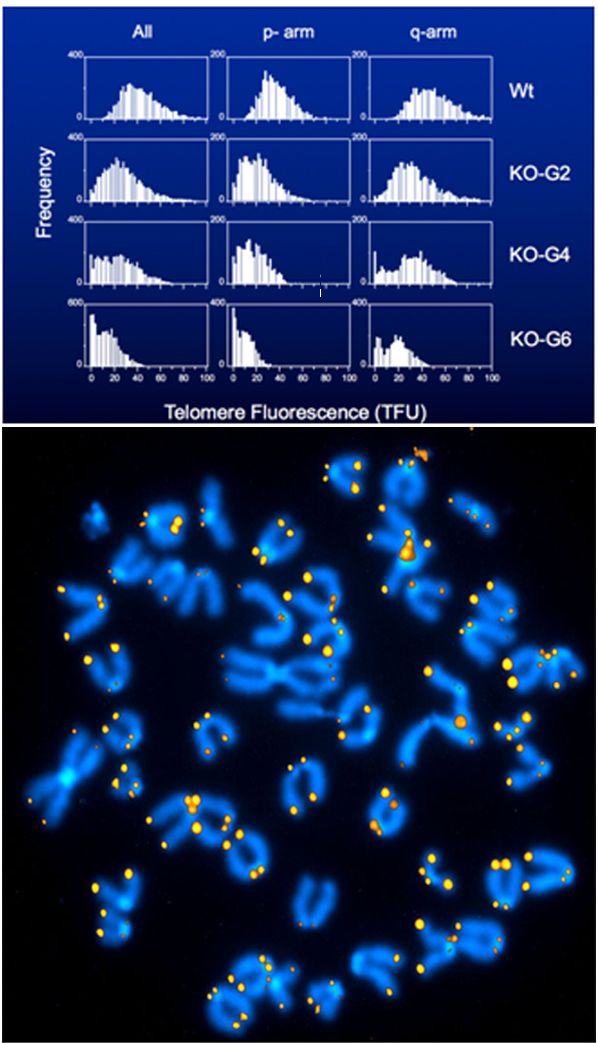

With PNA and Q-FISH tools, we performed a number of important studies, the most cited being our contribution to the study of the telomerase KO mouse (46) ( > 2000 citations, including the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine - Advanced Information Report). This paper was already under review at Cell when we got involved. Our findings significantly changed the message, essentially from “telomerase is not as important as we believed: it can be knocked out without consequences” to “telomerase KO mice lose 5 kb of telomeric DNA with each generation and uncapped telomeres at late generations cause fusions and genome instability”. See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Telomerase KO mice lose about 5 kb of telomere repeats per generation. Q-FISH analysis of embryonic fibroblasts of the indicated, subsequent generations of telomerase KO mice. 1 TFU corresponds to 1kb of telomere repeats. Note that in WT animals all chromosomes are “capped” with readily detectable telomere repeats, whereas at generation 6 (left and right panel) many chromosome ends have no telomere repeats and dicentric chromosomes with no telomere repeats at the fusion point are seen. A clear fusion is seen at 9 pm, right.

9. Described variation in telomere length at individual human chromosome ends

See Reference (47). We found that the average number of telomeric DNA sequence (TTAGGG) repeats on specific human chromosome arms is similar in different tissues from the same donor but can vary markedly between donors. In all individuals studied, telomeres on chromosome 17p were shorter than the median telomere length, a finding we confirmed by analysis of terminal restriction fragments from sorted chromosomes and by an independent study (48).

10. Reported that DOG-1, a specialized helicase, is required to maintain guanine-rich DNA in C.elegans

Intrigued by the large variation in the average telomere length between cells of individuals of the same age, I became intrigued by the genetic factors that regulate average telomere length. We focused on studies of mice in collaboration with Richard Hodes at NIH and identified a region on mouse chromosome 2 that is required to elongate the sort telomeres on chromosomes of M. spretus in crosses with M.musculus that have very long telomeres (49). However, this region was too large (>10 Mb) to knock out all the “candidate” genes in this region. Instead, we focussed further studies of one candidate gene, “Novel Helicase Like” in C.elegans, for no good reason other than that a knock-out strain of a very similar gene was already available in the lab of Ann Rose at UBC. This turned out to be a very fortunate choice as we found that the KO animal had a striking genome instability phenotype: deletions throughout the genome that invariable started at the 3’ end of poly-guanine tracks longer than 18 nucleotides (5). We renamed the gene Dog-1 (for deletions of guanine rich-DNA) and we postulated that the helicase encoded by Dog-1 might be required to resolve guanine quadruplex (G4) structures during replication. This pioneering work allowed us to deduce the function of a helicase protein from the very specific “deletion signature phenotype” observed in its absence. This work has stood the test of time and others have shown since that the human homolog of DOG-1 (FANCJ) also is required to prevent instability at G-rich DNA (50,51).

11. Cloned and described the function of RTEL1, a helicase required for telomere maintenance

Encouraged by our findings in C.elegans we decided to knock-out “Novel Helicase Like” in the mouse in collaboration with Andras Nagy and Hao Ding in Toronto. We could demonstrate that this gene is indeed a major regulator of telomere length and we named the gene accordingly: Regulator of telomere length (6). This work has also stood the test of time and recently patients with mutations in RTEL1 have been described by several groups (38,39). Such patients have very short telomeres and often show bone marrow failure similar to patients with mutations in telomerase genes such as TERT or TERC.

12. Founded Repeat Diagnostics, a company that provides clinical telomere length results

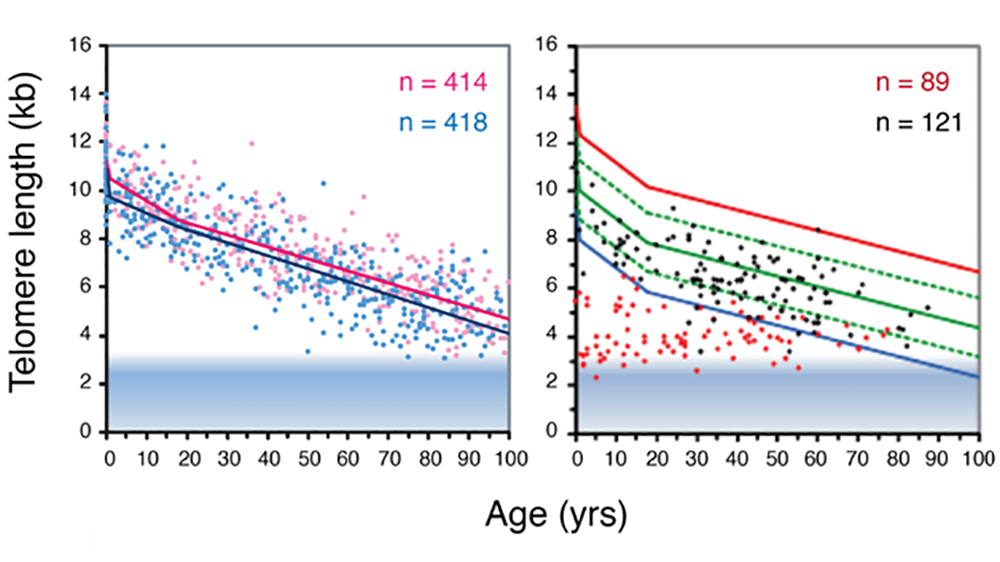

We developed and perfected a method to measure the average length of telomeres in specific nucleated cell types in peripheral blood using PNA probes, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and flow cytometry, a technique we called Flow FISH (52, 53). With this method, we showed that there is a large variation in the average telomere length between individuals of the same age and that the most dramatic decline in telomere length occurs in the first few years of life (Figure 3). Interestingly, at birth and throughout life the average telomere length was found to be longer in females than in males (3) and Figure 3, left). Based on reported gene expression in cells from female embryos, I recently proposed that such differences could be established before embryo implantation (54). In collaboration with hematologists and geneticists at NIH, we established that the telomere length in patients with genetic defects in telomere pathway genes, such as TERT, TERC, RTEL1 and others could readily be distinguished from patients with other causes for their bone marrow failure (reviewed in (55). Because our flow FISH measurements could also distinguish carriers from telomerase mutations from siblings without such genetic defect (Figure 3, right), we were soon overwhelmed by requests from clinicians to perform diagnostic Flow FISH experiments in our research lab. This clearly was not ideal, and I decided to set up a company, Repeat Diagnostics Inc., to provide clinical telomere length measurements. This company was not set up to generate a profit and has seen steady growth over the years. Currently Repeat Diagnostics employs 5 people and is processing 10-20 samples per day for clinicians around the world looking after patients suspected of inherited or acquired “telomeropathies”. My current ideas about the role of telomeres and telomerase in aging and cancer are summarized in two review papers (4, 56).

Figure 3. Telomere length decline with age in human lymphocytes in peripheral blood measured using flow FISH. The left panel shows that a difference in average telomere length between females (pink) and males (blue) persist throughout life. The right panel shows the telomere length in heterozygous carriers of a mutation in either the TERC or the TERT gene (red) and their unaffected siblings (black). Blue line: bottom 1 percent of normal telomere length at indicated age. Figure adapted from (3).

13. Proposed the “silent sister” hypothesis

In our hunt for genes that regulate telomere length we had discovered two genes encoding similar helicases, Dog-1 (5) or FANCJ in humans and RTEL (6). For both helicases, we proposed a role in the replication of guanine-rich DNA: the unwinding of single stranded DNA folded into guanine quadruplex (G4) structures. Long poly-guanine tracts in the C.elegans genome are much more abundant than would be predicted by chance (57), raising questions about the biological role of G4 structures in biology. One possibility is that G4 structures, perhaps arising stochastically during replication stress in the genome and at telomeres, result in epigenetic differences between sister chromatids. Delayed replication of the DNA template strand with the G4 structure is expected to result in asymmetric distribution of parental nucleosomes onto sister chromatids. Epigenetic differences between sister chromatids is at the heart of the “silent sister hypothesis” (7).

14. Discovered that sister chromatids can be distinguished by parental DNA template strands

In order to test the silent sister hypothesis (as proposed in number 13), we needed to distinguish sister chromatids in paired daughter cells. The solution we found was based on the Chromosome Orientation (CO-FISH) technique developed by Ed Goodwin and colleagues in the 90’s (58). Specifically, we found that sister chromatids of mouse chromosomes could be distinguished using PNA probes specific for the large unidirectional arrays of major satellite sequences in such chromosomes (59).

15. Developed the single cell Strand-seq method

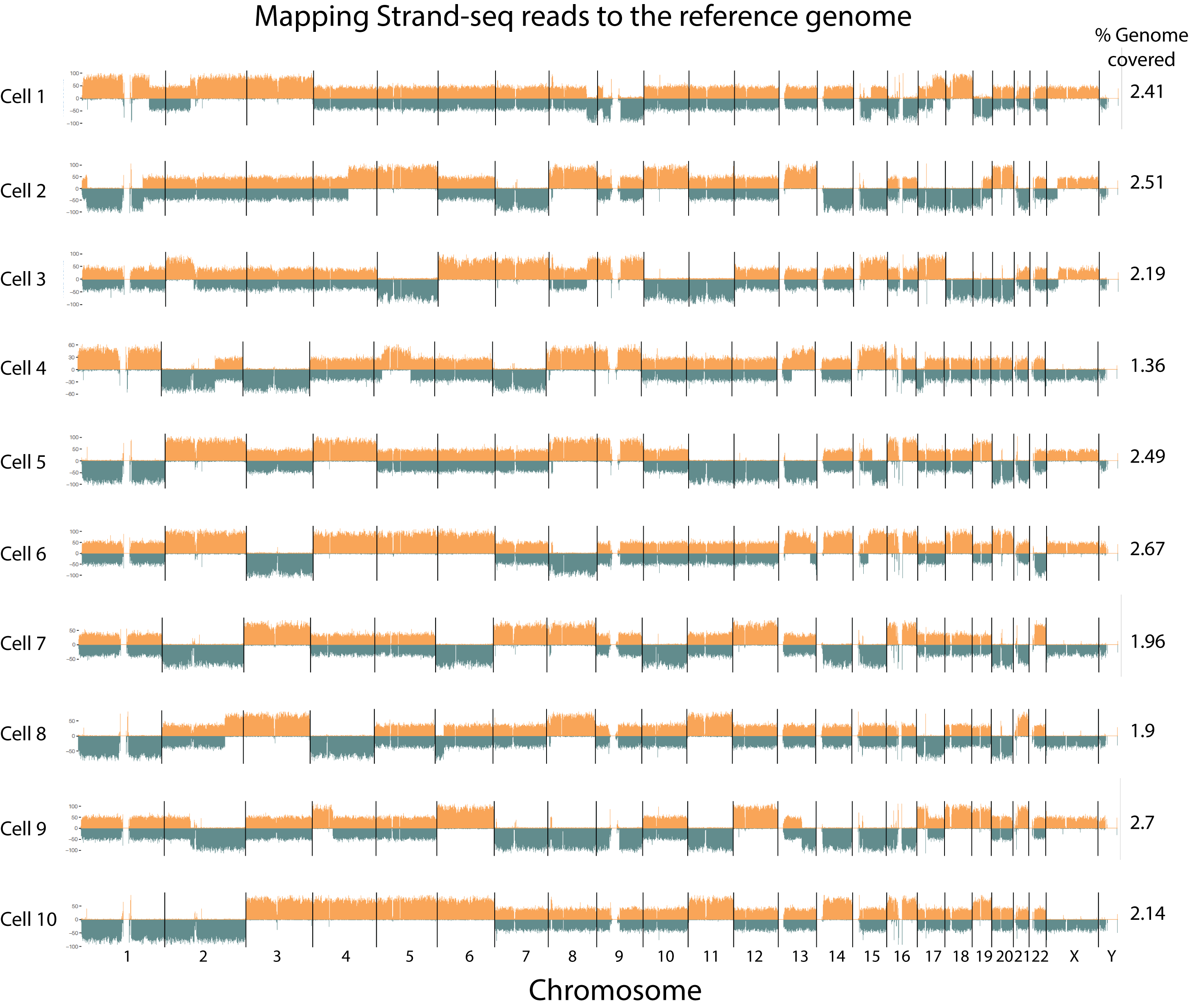

Based on the results describe in our Nature paper (59)described under Ad 14, we mustered the courage to develop a single cell DNA template strand sequencing (Strand-seq) technique (8). At the time, we could not have predicted the wide range of applications that this new technique would have outside our initial goal: to reliably distinguish sister chromatids in order to put the “silent sister” hypothesis to the test. The key features of Strand-seq results are illustrated in Figure 4. Various applications are discussed below.

16. Generated the first comprehensive maps of polymorphic inversions in human genomes

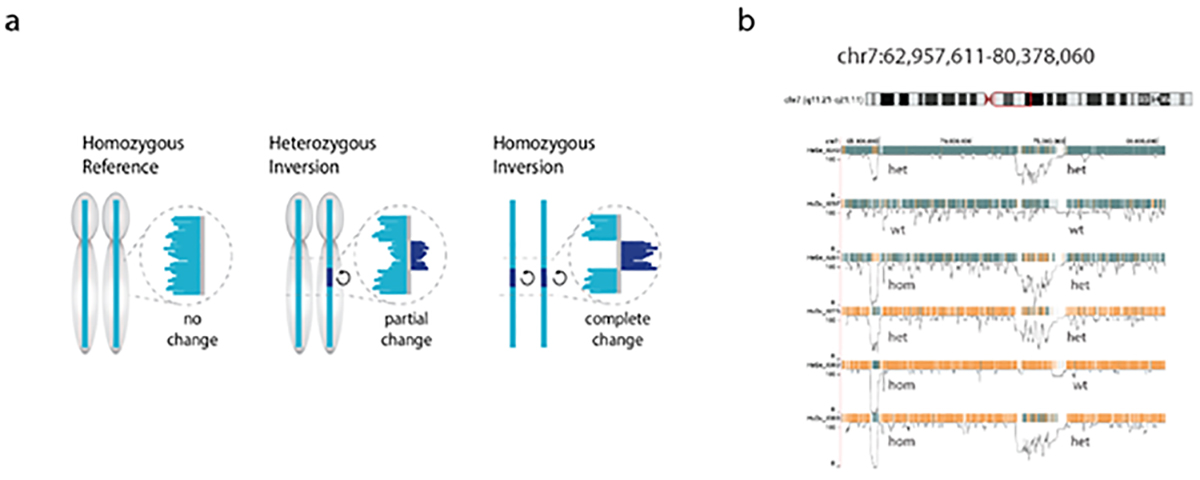

My lab generated the first comprehensive map of polymorphic inversions in the human genome. This work, spearheaded by Ashley Sanders when she was a graduate student in my lab, was published in 2016 (13).

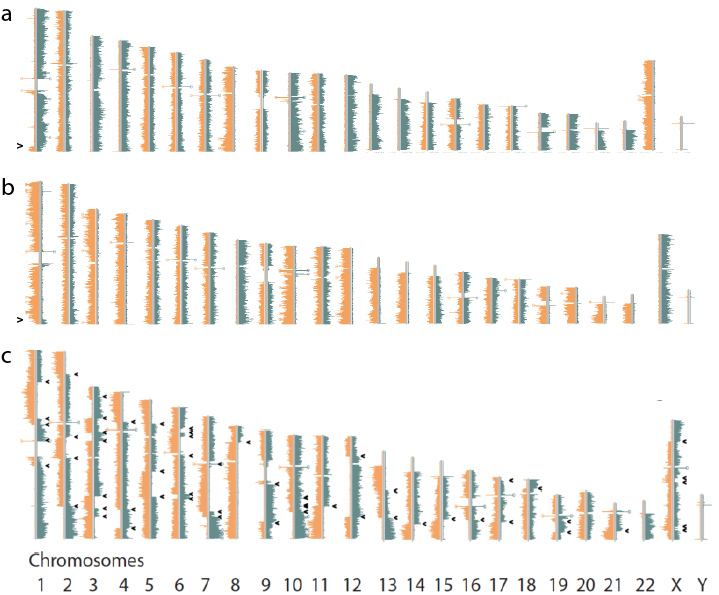

The principle of the method and an example of results are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Sequence reads generated by Strand-seq map either concordant with the human reference genome sequence (a, left) or map to both strands of the reference genome (reflecting a heterozygous inversion (a, middle panel) or completely to the opposite strand of the reference genome reflecting a homozygous inversion (a, right panel). Polymorphic inversions in the human genome generate a large amount of genetic diversity between individuals (48) as is shown in b for a 20Mb segment of chr 7 (red box) for 6 individuals. Note that the role of this type of genetic diversity is largely unexplored because of the difficulty to generate genome-wide information about polymorphic inversions using other sequence modalities.

17. Developed novel ways to establish haplotypes along entire chromosomes

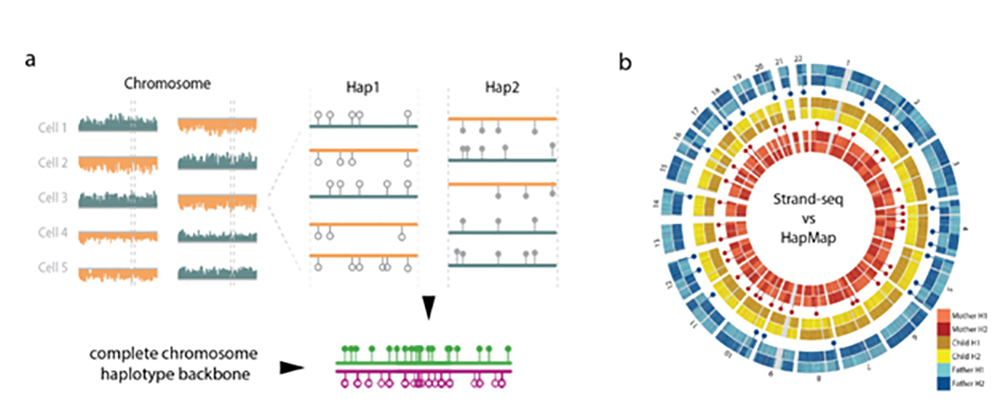

The diploid nature of the genome is often incompletely represented in “whole genome sequence” analysis, where a genome is typically represented as a set of unphased variants with respect to a reference genome. However, important biological phenomena such as compound heterozygosity and epistatic effects between enhancers and target genes can only be studied when haplotype-resolved genomes are available. Hence a method that can produce dense and accurate chromosome-length haplotypes at reasonable costs is highly desirable. Using a well-studied trio from the HapMap consortium we showed that Strand-seq allows for accurate phasing along entire chromosomes (12). The principle of this method and results of phasing of the trio family members are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. a) Strand-seq provides a physical haplotype map of SNP’s along entire chromosomes. Multiple cells with Strand-seq sequence reads mapping to both strands of the reference genome for a given chromosome (orange and blue) are used to assemble haplotype backbones (49). Such chromosome-long haplotypes correspond accurately (>99%) with HapMap reference data for a child (b, yellow) but not her parents (father blue , mother red), where Strand-seq reveals the location of parental meiotic recombination events (resp. red and blue dots). The haplotype backbones generated by Strand-seq allow complete phasing of human genomes when combined with other type of sequence data (e.g. 10X or PacBio data, 50).

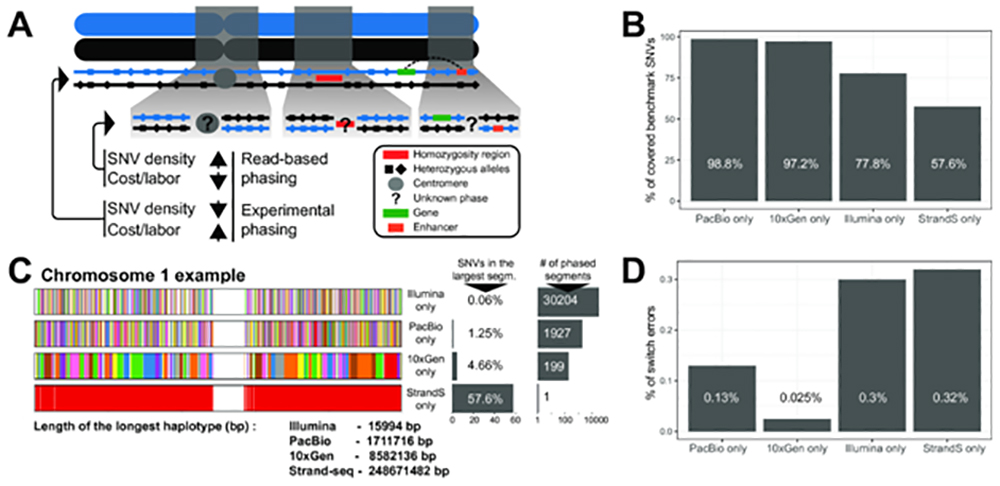

When combined with other type of sequencing data, Strand-seq allows near complete phasing (>99% of SNP’s) of human genomes (Fig 7, from (17).

Figure 7. A) Two homologous chromosomes are shown (blue and black). Experimental phasing approaches like Strand-seq can connect heterozygous alleles along whole chromosomes, however, at higher costs (time and labor) and lower density of captured alleles. In contrast, read-based phasing can deliver high-density haplotypes, but only short haplotype segments are assembled with an unknown phase between them. B) Barplot showing the percentage of phased variants, for each sequencing technology, from the total number of reference SNVs (Illumina platinum haplotypes). C) Graphical summary of phased haplotype segments for Illumina, PacBio, 10X Genomics and Strand-seq phasing shown for chromosome 1. Each haplotype segment is colored in a different color with the longest haplotype colored in red. Side bargraph reports the percentage of SNVs phased in the longest haplotype segment. D) Accuracy of each independent phasing approach measured as percentage short switch errors in comparison to benchmark haplotypes.

18. First to map the genomic location of sister chromatid exchange events in Bloom syndrome

Although Strand-seq data are in high demand, the preparation of single cell Strand-seq libraries is technically challenging (9). Variable results and limited informative reads have hampered the widespread application of the Strand-seq method despite its obvious theoretical appeal. We recently reported a simplified “one pot” (OP) method to make Strand-seq libraries that overcomes many of the previous technical challenges (10). Specifically, we developed a nanoliter-volume protocol in which reagents are added cumulatively, DNA purification steps are avoided, and enzymes are inactivated with a thermolabile protease. OP-Strand-seq libraries capture 10%–25% (10) of the genome from a single cell with reduced costs and increased throughput, opening up a wide variety of studies that are being pursued in collaboration with investigators in and outside Vancouver and Canada. A typical result of our current Strand-seq results is shown in Figure 8.

19. Assignment of alleles to the parent of origin. More information

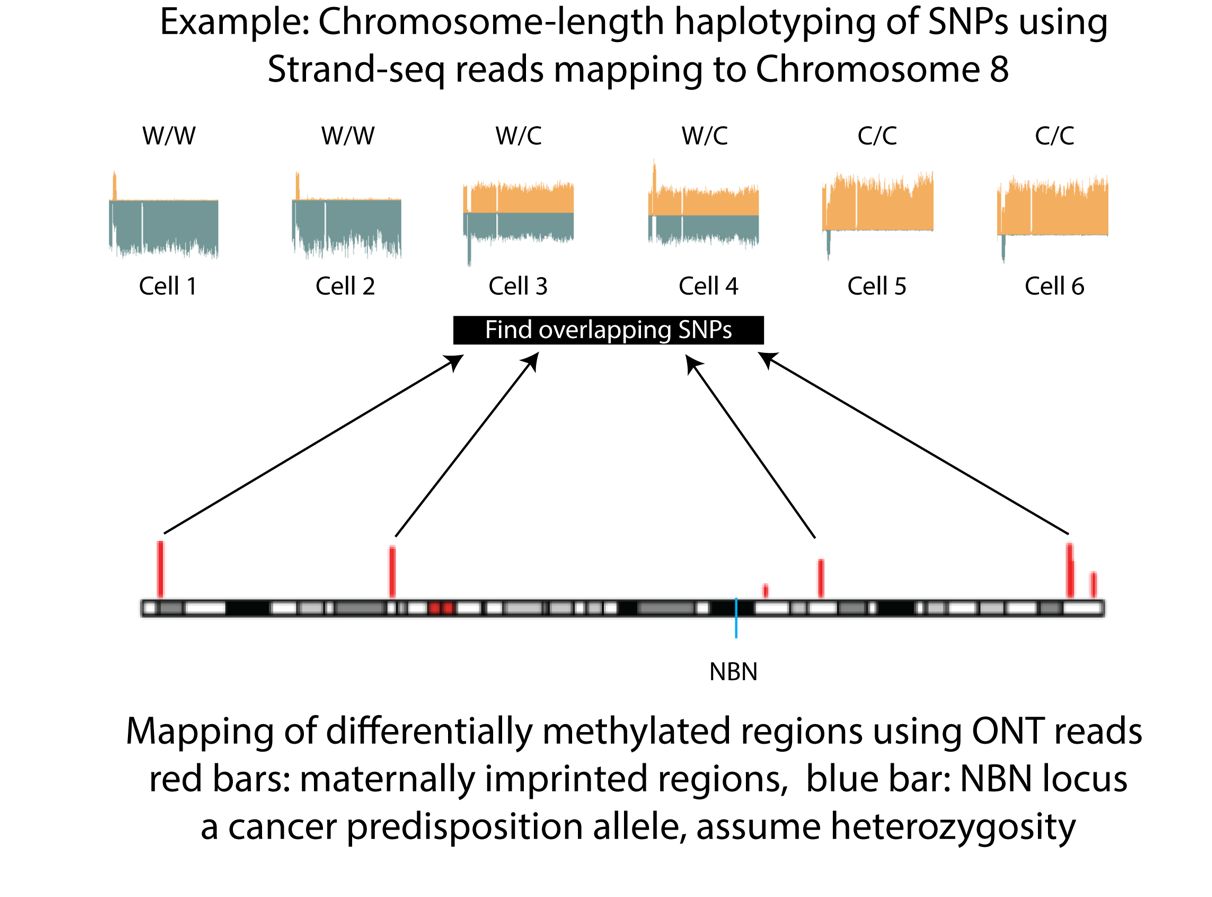

Genetic testing can inform a patient’s inherited risk for disease. However, predicting which side of the family an autosomal variant comes from is a key limitation of current technology. Inability to determine a variant’s parent-of-origin (PofO) (i.e., if it is maternally or paternally inherited) can lead to uncertain patient management and ineffective genetic testing of family members. We have developed a protocol using Oxford Nanopore Technologies’ long read sequencing (ONT-LRS) in combination with chromosome-length haplotyping enabled by single cell Strand-seq to allow, for the first time, PofO haplotyping without any sequence information of the parents (15). The principle of this method is shown in Figure 9.

Cells with reads mapping to opposite strands of the reference genome for a particular chromosome occur at a frequency of around 50% of cells. Such cells can be used to assign the parent of origin haplotype for that chromosome using parental imprints detected by Oxford nanopore long reads (15).

References

-

4. Lansdorp PM. Telomeres, aging, and cancer: the big picture. Blood. 2022;139(6):813-21.

7. Lansdorp PM. Immortal strands? Give me a break. Cell. 2007;129(7):1244-7.

44. Lansdorp PM. Telomeres, stem cells, and hematology. Blood. 2008;111(4):1759-66.

56. Lansdorp PM. Telomeres, Telomerase and Cancer. Arch Med Res. 2022;53(8):741-6.

Return to Dr. Lansdorp's profile:

BC Cancer Foundation is the fundraising partner of BC Cancer, which includes BC Cancer Research. Together with our donors, we are changing cancer outcomes for British Columbians by funding innovative research and personalized treatment and care.